Paintings as Ethnographic Tools

A lens into Crimean Tatar life and cuisine at the turn of the 20th century

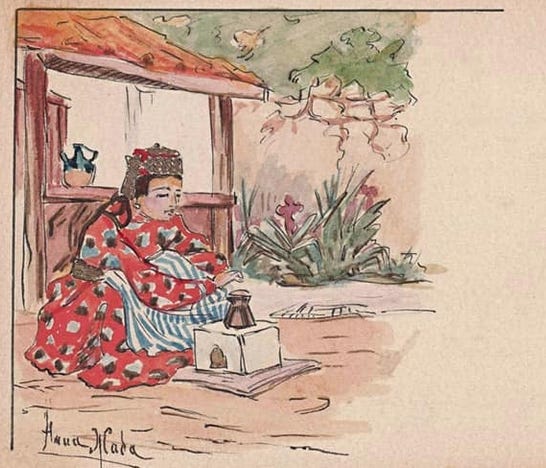

I stumbled upon Nina’s work while doing research on Crimean Tatar cuisine and its history. One day while I was using Google Images, a stunning watercolor of a Crimean Tatar woman rolling out dough populated the search results. I couldn’t look away, I was mesmerized. This led me to discover one of the most interesting artists of the 20th century, Nina Konstantinovna Zhaba.

Who is Nina Konstantinovna Zhaba?

Nina Konstantinovna Zhaba was born in 1875 Tbilisi, Georgia to a noble Russian ambassador to Constantinople father, Constantine Zhaba, and a music and drawing teacher mother, Emma Jürgenson. She had three siblings—two brothers, Alexander Zhaba (1860-1920) and Alphonse Zhaba (1878-1942), a painter, and one sister named Maria.

She attended and graduated from St. Petersburg Academy of Arts in 1906 and traveled to the city of Bakhchysarai in Crimea, Ukraine (the former capital of the Crimean Khanate) to sketch. As soon as she arrived she fell in love with the city of Bakhchysarai. She also met and married her husband, Maksoud Osmanov, a Crimean Tatar later that year. Nina ended up moving there permanently and continued to live in Bakhchysarai until 1924—teaching drawing at a local school.

Unfortunately, her life was also full of tragedy. In 1924, Nina’s husband was brutally murdered. According to family history or lore, Maksoud was sitting in the street one day, and a passing Soviet officer asked for his stick, Maksoud refused to hand over the stick, and the officer shot him in cold blood. The story of his death was told by Nina’s great-niece, or her brother’s great granddaughter, Yevgenia Drygo (1962-2020).

After his death, Nina moved to live with her brother in Leningrad (St. Petersburg), but tried to visit Bakhchysarai every summer. Nina and her brother both died in 1942 during the siege of Leningrad.

The Ethnographic Value of Her Work

Nina’s work wasn’t given the proper recognition it deserves during or even after her death. Her works are rarely exhibited. It wasn’t until 2021 that the Bakhchysarai Palace-Museum hosted an entire exhibition of her work in their collection. The exhibition came with a catalog of which there are only 100 published copies called Nina Zhaba's drawings in the collection of the Bakhchysarai Museum-Reserve.

I’m not going to speak to the artistic value of Nina’s works, I will save that for a later time, but I do want to emphasize how incredibly important her watercolors are for studying and understanding the culture of Crimean Tatars in the first quarter of the 20th century.

In her 18 years of living in Bakhchysarai, Nina painted and drew hundreds if not thousands of miniatures depicting architectural monuments, domestic/public spaces, and endless scenes of Crimean Tatars and their life. This has made her works of particularly high value to ethnographers, historians, Crimean Tatar art historians, and food historians!

Nina's works are now used to study the traditions and customs of Crimean Tatars in the early 20th century. Her works are helping us understand what the Crimean Tatars of the early 20th century wore, ate, did in their daily lives in and outside the house. Crimean Tatar editor, Zera Bekirova, says “In them (Nina’s watercolors) you can see the life of the Crimean Tatars, you can see what they did. There are men who lay out tobacco, a man who sells grapes, a milkman, and women who read books. This, by the way, is the answer to those who say that the Crimean Tatar women were uneducated."

In the 1930s, Nina published a series of postcards called From the life of the Crimean Tatars. These postcards were of an especially high importance to Crimean Tatars themselves, who were forcefully deported from their homeland in 1944 to Uzbekistan. Forceful deportation of Crimean Tatars is called Sürgün or Soviet Genocide. Crimean Tatar literary critic, Gulnara Seitvanieva, remembers her grandmother showing her one of the postcards when she was little in Uzbekistan—it was one of the only things they had on them while in exile that connected them to their homeland. Ulvie’s grandmother even referred to some of the people who were illustrated and depicted on the postcards by name.

Life of Crimean Tatars in the early 20th Century:

I want to share some of my personal favorites. These watercolors and postcards were made sometime between 1906 and into the 1930s. Looking through these works gives us a sense of how Crimean Tatars occupied their time across all ages, genders, and socioeconomic levels. We can see how they ate, what they ate, what equipment they used to prepare dishes, and even what dishes they used to serve and store food.

Baking News!

Cheesecake orders through the end of July are now OPEN!

How fascinating! You’re reminding me a novel I loved years ago, too, that you might like: https://www.europaeditions.com/book/9781609450069/the-hottest-dishes-of-the-tartar-cuisine